Barcelona and their fixation with space

The Catalan side take a slender lead going into the second leg at Spotify Camp Nou. How did they tackle Chelsea's defensive tactics?

“We had a disappointing start and gave away a 0.03 xG chance, brilliant individual play, but we grew into the first half, scored a goal that was offside, had a big chance with Guro, and you have to be perfect to beat this side.”

Advantage Barcelona. Emma Hayes summed it up perfectly when she said you have to “be perfect” to beat Barcelona.

If beating Barcelona is difficult, doing it at Spotify Camp Nou is practically mission impossible. So Chelsea needed a result at Stamford Bridge but came away with a loss. The tactical match-up was intriguing and one which Barcelona eventually had the answers for. So how did it unfold?

Chelsea’s press and marking approach

Any questions on how Hayes was going to approach this game was answered before the ball was kicked. The lineup indicated Chelsea’s intentions with a 3-5-2 system that initially looked like it could have been a 4-2-3-1.

The objective was to limit Barcelona’s attacking threat by creating a vacuum of space in the defensive third, especially around the half-spaces where Barca prefer to operate. Chelsea opted for a switch between a zonal and man-marking approach depending on the situation, counteracting Barcelona’s 3-2-5 attacking on-the-ball structure, shifting the ball to the middle to suffocate the space and create a brawl.

The more they committed Barca centrally, the more chances they had of regaining possession and launching a counter-attack. The idea was to limit their wide attackers and create a stronger central base given the rotations Barcelona make to their wingers which creates superiority.

What was interesting was the dual roles the defence had in switching markers.

Barcelona wanted to use their pacy wide attackers and full-backs to pressure Chelsea in the pocket and isolate the full-backs, but by having the extra centre-back and pivot player, Chelsea wanted to negate the half-space area and win back possession there to counter-attack through Guro Reiten and Sam Kerr.

The double pivot was an important cog in the whole system. Both Erin Cuthbert and Melanie Leupolz were tasked with patrolling the left and right defensive half-spaces to create the fourth overload player with the wing-back and centre-back. Despite this, Leupolz’s failure to get tight in the right half-space was partially to blame for Graham Hansen’s goal.

Jelena Čanković was a supporting figure to both and was positioned accordingly. Her role was more of an attacking, creative outlet on the ball but more importantly, she was a pressing trigger off it. She added to the numerical advantage Chelsea wanted in the high-pressing zones and these pressing areas were essentially the space across the opposition's defensive midfield line. Any time a Barcelona player stepped in to collect from the centre-backs, Čanković would press the ball carrier – particularly the defensive midfielder. I’ll expand on this more in the next section, but suffice it to say Čanković’s role here forced Barcelona to make adjustments that theoretically benefited Chelsea.

Barcelona’s front three consisted of Caroline Graham Hansen, Salma, and Geyse who all possess speed and the dangerous ability to run in behind. Chelsea understood the need to block off the space and by positioning themselves a little bit deeper, they ensured they compensated for the lack of pace. They parked the wide centre-backs to a dual role of marking the Barca wingers and central striker while the full-backs were responsible for the widest attacking player – be it Fridolina Rolfö, Salma, or CGH – and coax them into moving in centrally.

This was a surefire way for Chelsea to congest the space Barcelona looked to operate in and limit the running interchanges between the ball-sided central midfielder and inverted winger. Barcelona relied heavily on midfield runners and stopping their runs was equally as important. Aitana Bonmati pushed up into the half-spaces as the primary midfield runner but was nullified by the wall of Chelsea players.

Barcelona’s build-up concerns

“They make the most of transitions, they don’t fold under pressure. We have to be patient offensively.” – Jonatan Giraldez

It didn’t take long for Giraldez’s prematch comments to come to fruition. Their patience only needed to last four minutes when Caroline Graham Hansen produced an incredibly ferocious shot cutting in from the right to give Barcelona an early 1-0 lead. Despite Chelsea’s tactical setup, the Norwegian winger created one of those game-changing moments, giving Barcelona an early advantage and a cushion to play with a lot more composure.

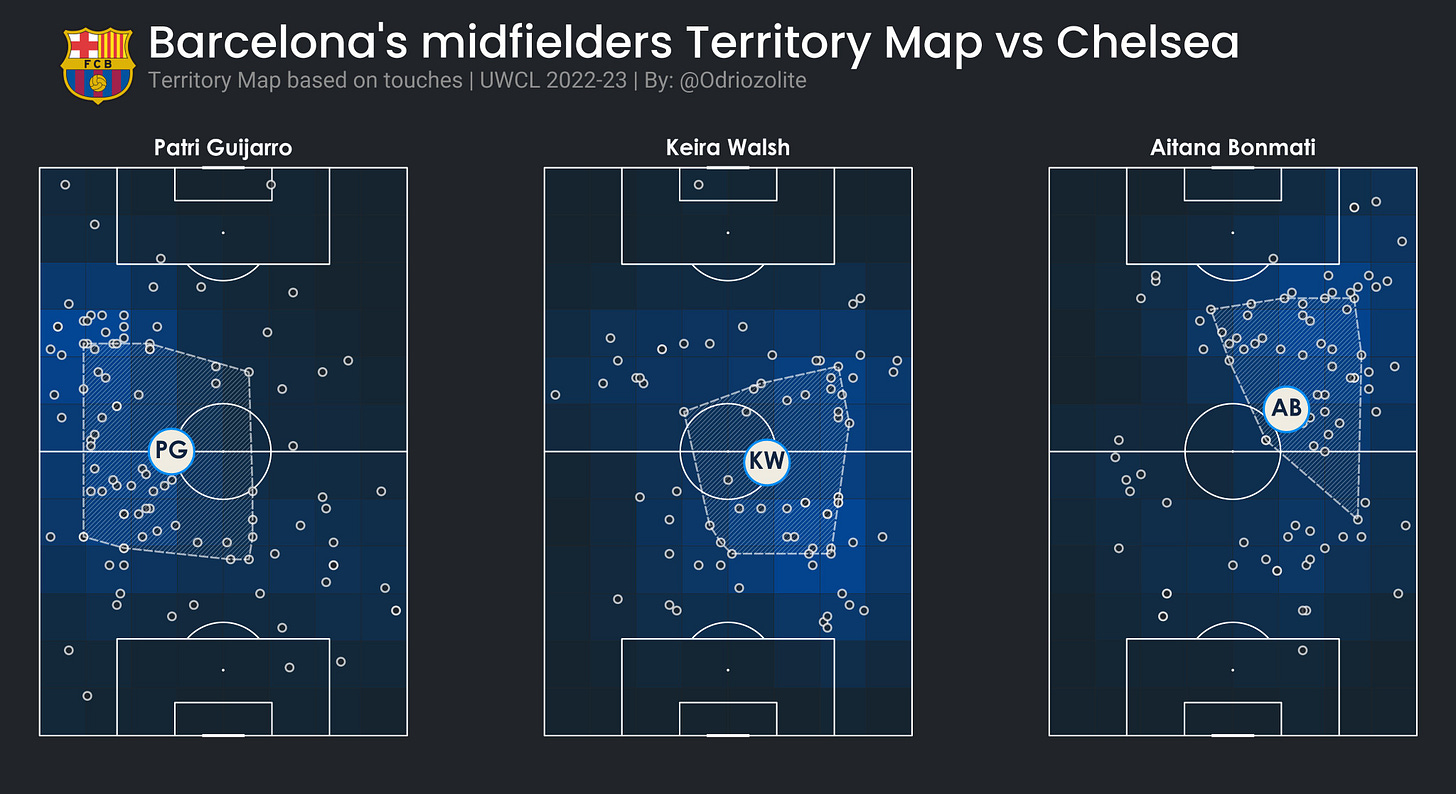

Barcelona’s 4-3-3 was built around the ever-reliable trio of Aitana, Patri Guijarro, and Keira Walsh who are at the crux of their overall build-up. There was good coverage of defensive security and attacking intent with each player showing a concise role in their territory map.

The system relies heavily on the deepest lying midfielder – Keira Walsh – to initiate the first wave of build-up towards the middle and final thirds. Once she receives the ball, it’s up to her to find one of her central midfield partners or go wide to the furthest forward full-back. Barcelona prefer to keep their passes short to medium rather than playing long diagonals, prioritising control over progression. This isn’t to say that progression isn’t a priority, but their core philosophy of control breeds progression inherently.

"It was probably more about Patri getting on the ball in the first half, when you're marked it's about creating space for other players. It's not easy when someone's following you around the pitch" - Keira Walsh on being shadowed by Jelena Čanković in the first half.

Walsh initially struggled, given how Čanković was tasked with cover-shadowing the defensive midfielder and denying any vertical progression. Knowing how important Walsh is to Barcelona’s build-up, Čanković did an excellent job with the second line of press which was most integral to Chelsea regaining possession in the final third. If there’s any place where Barcelona can be susceptible, it’s their defensive third against a high press, as was showcased to great effect by Lyon in the 2022 final.

As a result, Chelsea forced Barcelona to either go back to the centre-backs or bait them to go through the middle and force the duels. To counteract this, Patri dropped in to create a double-pivot next to Walsh to give them an extra player to help alleviate the pressure. This invariably allowed Barcelona to gain a better hold of possession, but they had to readjust and use quicker passes between the lines as well as players dropping into midfield to create that bridge between the midfield and attack.

Attacking adjustments in build-up

In build-up, it was tougher for Barcelona because of the partial success of Chelsea’s man-marking approach, but the two-player midfield left spaces on either side of them as a consequence, which allowed one of the wider players of the five to drop into and receive once the ball carrier broke the initial press.

The pace of Geyse, Salma, and CGH was to used to run in behind the Chelsea defensive line but also to attempt to pull players out of position into these pockets of space. Given the deeper positioning of the Chelsea backline, the front three rotated positions by moving between the half-space, deeper midfield pockets, and central areas to create unpredictable movement patterns. This change of position was there to ensure there was minimum width created to still get their strongest players in good goal-scoring positions. Any time Chelsea shifted their defensive shape towards one side, Barca just looked to switch the point of access quickly to exploit the under-utilised space.

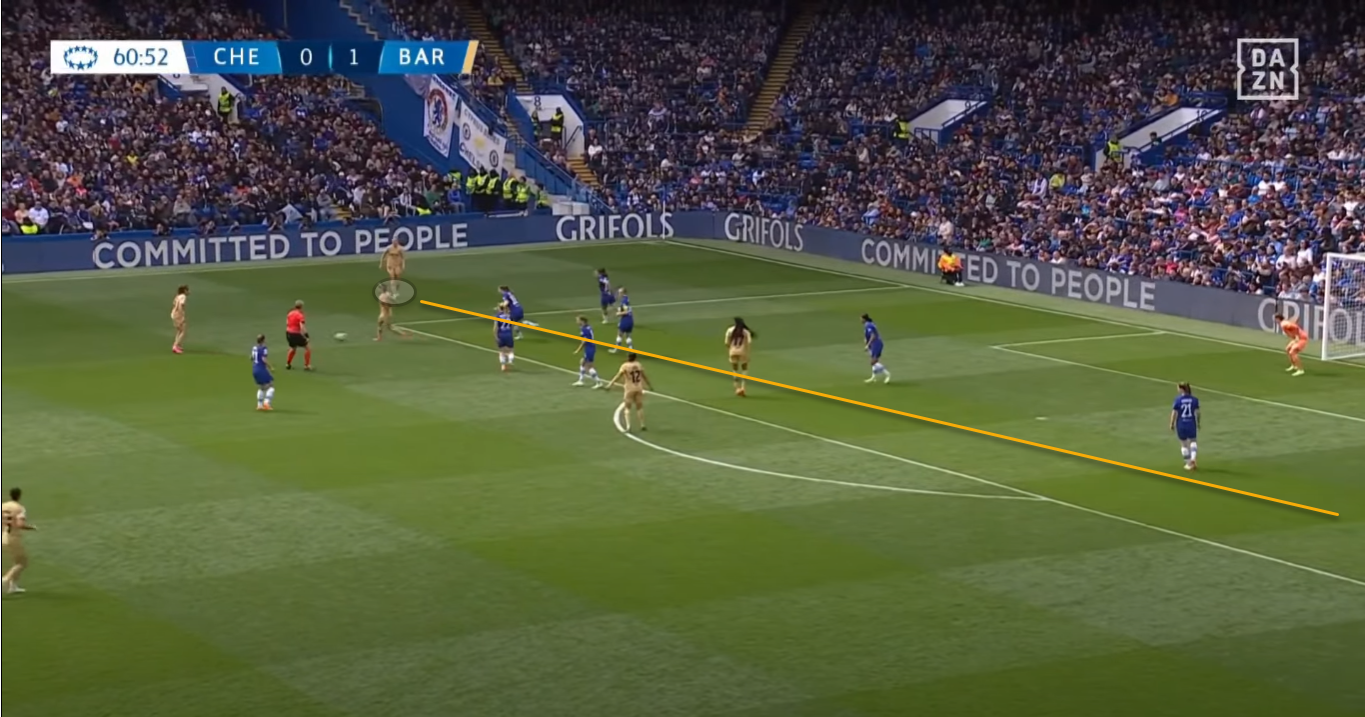

Barcelona’s threat was emphatically omnipresent and in the 58th minute, they showed their technical proficiencies by pushing Rolfö up higher alongside Patri and Salma. A simple adjustment of just pushing the team 5-10 yards higher and playing quicker incisive football meant the Catalan side were now creating much quicker passing exchanges.

Here, they played with Leupolz, Perisset, and Mjelde defending the right half-space and wide area against Rolfö, Patri, and Salma. Cuthbert shifts across but the neat, intricate passing takes out the extra player. The pass goes into Geyse who comes across from the middle and plays a give-and-go with Salma who finds a run in behind Mjelde and Eriksson.

Minimum width - Wide players are key

It’s from this base that Barcelona effectively transformed into their preferred 3-2-5 attacking structure in transition and create a flat front five, using their front three, a central midfielder, and a full-back. The constant, fluid movement of the front five is meant to overload and create interchangeable passing triangles to work around the flat defensive line and generate space. Isolating full-backs and central defenders is Barca’s priority and the technical skill of their attackers is key in making this happen.

But how did Barcelona make this happen?

A concept widely attributed to Erik ten Hag’s Ajax and Manchester United is that of minimum width. Its most basic definition is to reduce the spaces between the players in your attacking line. You want to keep a shorter distance between your players whilst achieving width to ensure the ball travels less and that players are closer to taking a shot-taking action. Jon Mackenzie explains this concept much better and looks at why it’s a crucial chance-generation tactic of positional play.

Giraldez adapted this same concept to his own team by closing the gaps between the players by pulling more players closer together to create chances. This became much more apparent when Mariona Caldentey was substituted on for Geyse, giving Barcelona a wide playmaker that drifts into the interior channels.

The first screenshot shows the Barcelona players wider apart in the first half whilst they become a bit more compact in the second half as seen in the second screenshot.

Notice how close the Barcelona players are on the left with Graham Hansen's position (screenshot 3) much closer to Chelsea’s goal than what would have been in the first half.

This created a basis for Barcelona’s changed 3-5-2 shape in the second half and it explains why they started to get more joy in the final third.

It says a lot about what it takes to stop Barça when they played in what seemed like first gear for the majority of the match.

Photo by Alex Broadway/Getty Images