How Lyon & Chelsea have tactically deployed their wide forwards

Both teams have used their wide players in different ways but is there a fundamental principle each team relies on as a base?

The evolution of the attacking roles has been an ever-changing process thanks to the influence of footballing cultures and the women’s game is no different. Focusing on the women’s game, there have been some interesting styles that have emerged this season using the wide players. Managers from different parts of the world have changed the way teams attack in order to find innovative methods and creative solutions to create a seamless forward line with the players at their disposal. Different players have different strengths and sometimes it takes an unorthodox idea to extract the best out of them.

The rise of the false nine in the last decade was created to take advantage of excellent wide players. Similarly, the move from traditional wingers to more inside-forwards have become more prevalent in the modern game to the extent that players now need to be extremely fluid and versatile in their movements and position. This isn’t to say they need to excel in playing in other positions, but rather understand the intricate details. The idea of the evolved inside-forward comes from the trends seen in their construct and usage so far this season. Some of Europe’s top teams have found innovative methods to mould their forwards into unique tactical systems.

While defences now form part of the attacking structure of a team’s overall tactical plan, the way the forward operates go a long way into justifying how the rest of the team works. Each of the stronger teams in Europe’s top leagues harbours some of the best attacking players that are each integrated into distinct tactical systems, all created to extract the best out of them.

In some sense, the inside-forward can sometimes be seen as a very primitive role with their scope for tactical diversity limited even with their fluid freedom. The usual sight of a wide forward cutting inside and shooting is what we might think of at best, however, there are several examples of how teams are now evolving their use of these players and the role itself.

Their diverse use means coaches can leverage their strengths to tie in with the rest of the team. So if a team has more direct wide players, that puts more of an emphasis on possibly using more playmakers and box-to-box players in midfield with a mobile number 9. On the other hand, a playmaking wide player might suit having an attacking full-back coupled with an attack-minded central midfielder. Barcelona, Lyon, Chelsea, and Arsenal each have a unique style of using their inside-forwards.

The basic structure that uses an inside-forward is a 4-2-3-1, 4-3-3, and 3-4-2-1. The aforementioned roles can be used in each of these formations all taking advantage of the different strengths of the team. The passing links in these formations create multiple passing channels and connections between positions. The centre-forward link with the attacking midfielders and more. One of the most difficult things in football is often breaching the opposition’s compact defensive block and what the aforementioned teams have done is create a system that looks to unlock that.

To do this, managers have to come up with different tactics that will somehow outsmart and demolish a cohesive defensive unit. Creating a network of positive passes in the final third through deeper completions or intricate one-two passing exchanges are vital to the method.

The end result is often a penetrative pass or goal-creating sequence that produces a clear-cut opportunity. Having established the relative theory and understanding behind the tactics, let’s further examine what two teams have done to make this work in their own distinguished manner.

Olympique Lyonnais

Sonia Bompastor’s appointment was not only down to the poor performances but the lack of tactical flexibility under Jean-Luc Vasseur. The former Lyon manager was criticised for his tactics and it ultimately cost him his job. Ada Hegerberg’s ACL injury has meant there was a reshuffle in how Lyon lined up and last season saw a constant switch between Nikita Parris, Jodie Taylor, Melvine Malard, and Catarina Macario. The constant changes meant there was no continuity but it also felt as though there was no real plan in place. Bompastor used the summer window to reinforce her side with new signings whilst also coming up with a more effective strategy to make them thrive.

As a result, Lyon have scored 23 goals in D1 Arkema and three so far in the UWCL but more importantly, their overall play is much more pleasing. Bompastor has seemingly figured out a way to effectively integrate the forward players but interestingly enough, it’s how she’s utilised the wide players which are most interesting.

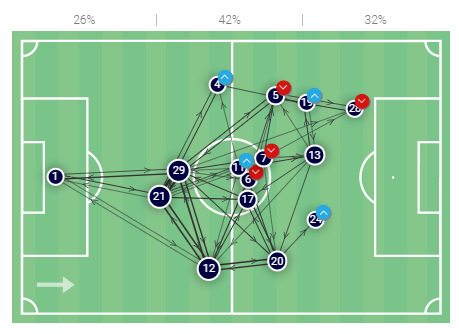

Their main setup has been a 4-3-3 but there’s also been the use of a 4-1-4-1 formation. This, as we’ve mentioned earlier, is a system that really unifies and enhances a team’s attacking potential. While there have been a few different variations in the forward line, the main attacking idea has remained constant. Bompastor wants the two of the three forwards to rotate positions and play closer together to create overloads whilst the opposite winger stays wide and provide a wide crossing angle. The passing network against Bordeaux highlights Cascarino (#20), Macario (#13), and Malard’s (#28) general positioning. There’s a distinction in their positioning that’s enough to illustrate their whereabouts in what was discussed.

The system relies on structured yet fluid rotations between the forwards. A lot of this has come between Malard and Macario who play as the left inside-forward and striker with Delphine Cascarino as the right-winger offering a crossing option. In this setup, it is Malard and Macario who interchange play and create passing exchanges to pull players out of position. However, Bruun is also another viable alternative in either position.

Inevitably, this creates positional overloads as the left-back is now free to make overlapping runs to add an alternative outlet. The other option is the right-sided forward finding opportunities to create balance but if there’s an opportunity to come inside, then the right full-back will make the run.

This is the underlying principle of the situation which hasn’t been an exact formula, rather an interpretation for the players to follow and execute.

The example here shows Malard and Cascarino both in wide positions but Malard’s first instinct is to cut inside while Cascarino maintains a wider position. Simultaneously, Signe Bruun (the starting centre-forward) moves towards Malard’s wide left position.

Alternatively, the inside-forward’s positioning also determines how the full-backs play. Lyon’s system have the full-backs as integral to their attacking output without having set rules to abide by. So in the case above, with Cascarino making an inward drive towards the box, Ellie Carpenter makes a marauding run overlap to cross in for Malard. Throughout this passage, Bruun was the conduit between Carpenter and Cascarino in the right half-space which opened space for Malard to drive inside as the striker.

Against Hacken, Lyon really tried to manipulate their disciplined back four and given that’s how modern defences operate, this sort of manipulative system is needed to ensure there is some sort of effective ball rotation that leads to penetrative outputs in runs and passes. The return of Hegerberg should give Lyon another excellent option, but that will play more around the channels than interchange positions. It will be interesting to see how Bompastor integrates Hegerberg into this system and whether we’ll see more tweaks to the current style of play.

Chelsea

Emma Hayes has opted to switch from a 4-2-3-1 to a 3-4-3 this season in a bid to get the best out of her attacking options. This change has prompted a narrower approach from her two number 10s or wide forwards depending on their initial starting position. This is important because Chelsea’s forward line relies on freedom and fluidity of movement to operate given there’s a more structured base behind them.

Under the 3-4-3 system, the width comes from the wing-backs and given Chelsea’s use of Guro Reiten and Erin Cuthbert in those positions, the front three really focus on rotations and movements to exploit space between the lines and bring in other players into play.

Part of the reasoning behind the switch to a three-at-the-back formation was to allow Chelsea to have more control in the interior channels in the final third. Since the inside-forwards favoured coming inside, the old system saw them overload the wide areas before creating goal-scoring chances. But given their defensive transition issues in the 4-4-2/4-2-3-1 and full-back conundrum, there was no harmony or balance between attack and defence.

However, the internal rotations by the inside-forwards now mean there is space for the wing-backs to run without being short on numbers at the back. The highlighted spaces in the graphic are where Chelsea’s inside-forwards prefer to operate in. This narrower initial position means they play closer to goal and as a result, it encourages more positional rotations with the striker. Pernille Harder, Fran Kirby, and Sam Kerr have nominally been their first-choice front three and the former two have consistently been seen switching positions with the Australian.

These movements have been crucial in helping the wing-backs settle and have a bigger impact in this 3-4-3. This is where width comes from and giving a player of Reiten’s calibre space only adds more threat to an already threatening attacking forward line. The constant ball rotation on the right saw Kirby drop deep to receive while Harder and Kerr were both on the same side. This passage of play and move to the right meant Kirby could switch play and afford the left wing-back acres of space to cross which resulted in a brilliant cross and headed goal. Notice how all three forwards end up being in close proximity of the six-yard box, making it difficult for the opposition to mark.

In addition to the inside-forwards staying narrow, the players are comfortable moving outside to open space for interior runs from the wing-backs. This idea of unpredictability means Chelsea are able to stretch teams, especially on the counter-attack. The movement of the two inside-forwards dictates a lot of their teammates’ decisions in terms of their movement. The wing-backs as we’ve seen have been a prime example of this sort of movement decision-making. You see Kirby stretch the pitch wide making Reiten direct herself into the inside left channel, managing a short pullback into the box.

To a large degree, Harder is the main benefactor and conductor of this system and offers Chelsea a much more direct option from her new left inside-forward position. Her ability to operate in these spaces closer to the box is reminiscent of part of her role at Wolfsburg as this ‘9 ½’. The heat maps are a comparison of Harder in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 seasons so far and while the sample size is smaller, there’s a lot more focus on playing closer to the box and affecting games. So far, the Dane has scored crucial goals like the equaliser against Wolfsburg and the first goal against Brighton & Hove Albion that proved critical.

Both teams have shown a propensity to use their inside-forwards in creative ways to garner favourable results. The different uses have shown how the strengths of the players at your disposal can be used to break down various opposition defences and ultimately dictate the rest of the team’s style. This is definitely the case with Chelsea more than Lyon.

However, Barcelona remain another interesting case study that requires a sole analysis dedicated to their use of inside-forwards with Mariona, Lieke Martens, and Caroline Graham-Hansen’s variations and how each one affects the side’s playstyle differently.

This prompts a wider discussion on how they have influenced sides to change their structure and a second article will be published dedicated to explaining their use of inside-forwards.

Photo by ADAM IHSE/TT News Agency/AFP via Getty Images